Corpuscle connections by Anika Gardner / Polyphonic Art by Stevan Howison

Anika Gardner

Anika is an emerging artist interested in the impact and intersection of cognitive science in art and society. Their aim is to develop an art practice that gives space to think and feel around isolated elements of robotic technology, without the entrapping of neoliberal consumer driven biases or need for a result. Currently Anika’s focus is on how our scientific understanding of the cellular mechanisms in the somatosensory (touch) system are being translated into technological apparatuses.

Anika completed a Bachelor of Creative Arts (Visual) at Flinders University and is currently studying a degree in Cognitive Science, minoring in Mathematics at Flinders University. Across the course of study Anika has been involved in a number of projects, most notably exhibitions in South Australia and a series of small bronze public art works for the City of Adelaide and the Department of Transport and Infrastructure. Anika was a recipient of the Helpmann Academy Graduate Award 2019 and Helpmann/City Rural Travel Award 2019. In 2021 Anika was awarded the Goolwa Public Art project by Helpmann, which they are currently working on, and a residency at George Street Studios in 2022. In February 2023 Anika undertook a residency at AADK in Blanca, Spain which provided them the space to pivot their practice into a more cognitive science inclined approach and where they began developing this project. They are set to do another residency at GILS in Iceland in June 2023.

.

Darting between studies in neuroscience and sculpture, and drawing from experiences as a tradie and metalworker, Anika Gardner gleans, programs and stitches in search of new syntheses. ‘Corpuscle connections’ is a sinuous body of work forged in the space between these diverse practices and modes of inquiry.

At its core, the exhibition responds to the emergence of soft machines - robots and haptic interfaces increasingly designed with flexible and adaptable tissues referencing human skin. The concept of introducing nociception in such interfaces - the neural capacity to discern and respond to stimuli such as touch and temperature shifts - is Gardner’s particular curiosity. With recent research increasing popular awareness of the body’s storage of traumatic events, and its passage through generations due to epigenetics, the ability for robotic intelligences to feel and respond to pain adds further ethical complications.

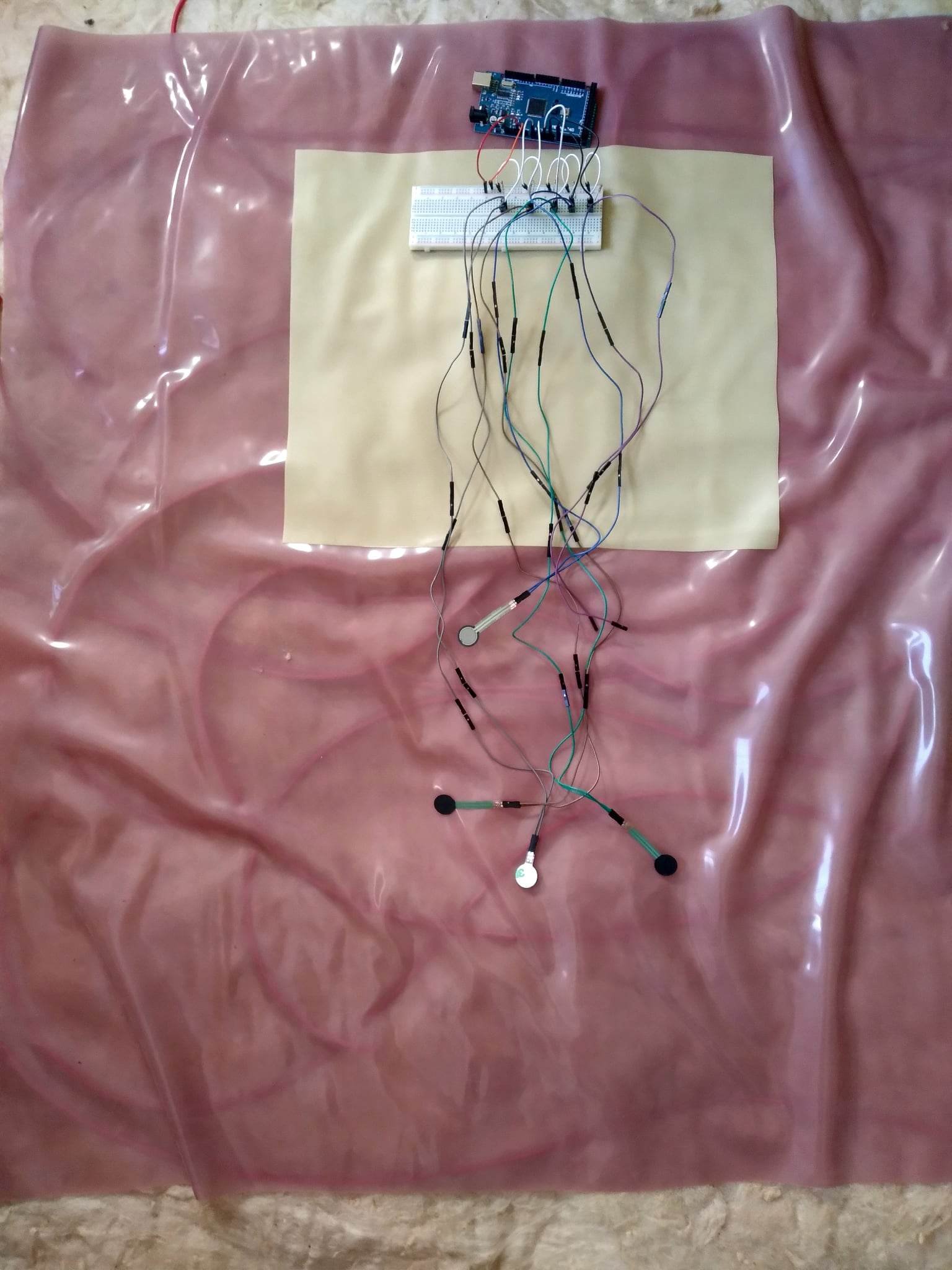

From this complexity emerges Bip 2.0 - the second version of a project begun in Blanca, Spain. Bip is a lengthy plane of patchworked rubber, a soft machine ready to assert boundaries with coded poetic commands. Their surface is an experiment in biomimicry, with tissue programmed to respond to trauma, creating a provocation around agency, intimacy and consent in a malleable material future.

On latex pools several cultural associations. As a pliable and wearable surface, it mediates a range of interactions in haptically charged spaces - on either end, the clinic (gloves) and the dungeon (fetish wear). Gardner’s use of latex is both rough and tender, rerouting its often-industrial applications to signal new forms of material kinship [1) - Gardner’s handwritten code forms a tattoo on Bip’s skin, emphasising touch as transformation.

Alongside latex, Gardner’s use of pink insulation, steel and sensors echo the material language of building sites, the metalworker’s studio and the laboratory. All elements contrast, like cells, by their degrees of permeability. The body of the exhibition, in fleshy hues, is dense, absorbent, sleek, thin, fragile, possessing boundaries that could yield or threaten friction. With increasing automation of labour and the advent of purpose-built ‘sex robots’, business and pleasure will not be immune from questions of human-machine consent, a reality which Gardner invokes at both industrial and cellular scales.

‘Corpuscle connections’ celebrates and complicates nascent science and technology, focusing less on Chat-GPT’s cerebral exchanges and the abstract dispersion of the Cloud, in favour of the physical. Gardner returns our attention to the body and the cellular space of sensation, advocating for feeling through human-machine interaction with sensitivity and renegade vigour.

Hen Vaughan

[1] Clementine Edwards and Kris Dittel (eds.) ‘The Material Kinship Reader’, Onomatopee, 2022.

Anika Gardner, E-skin formation, mixed media.

Anika Gardner, E-skin formation, mixed media.

Stevan Howison

The decision to become an Artist was made by myself thirty five years ago. I started with pencil drawings in the manner of literal Surrealism.Then I was very fortunate to study under John Barbour at the “Underdale” campus. At which time I was introduced to metaphor , sign and more generally to sculpture. Though I never lost interest in painting. I have found it difficult to sell painting and graphic work. But it is even harder to sell sculpture. But of course that is not why art is being made. I agree with Louise Borgeois that “Art is a Priviledge”And that it must be handled with “Devotion and Care”.

A long time ago when painters had really bad arthritis in their hands their assistants would tape the paint brushes to their hands so that they could go on and keep painting. One sees images of Henri Matisse in a wheelchair making his famous “ Cut Outs”. That is how it is with Art. The compulsion is very deep. I made paintings so encrusted with paint that they were too heavy to hang on the wall. And that they had to be exhibited resting in the floor. Using emulsions and aggregates. Or using unusual materials. Finding alternate paths . And this is always tied up with one’s psychology. Or aesthetic aspirations. Things that could be accomplished. One day one says to oneself “ Now I am going to paint the Stations of the Cross” It is deliberate. Or at least conscious. There is very little money in Art. One makes Art for aesthetic and psychological reasons. Many of my paintings are abstract. But the preference is for representation in paintings.

Stevan Howison is a generous man, he’s invited me to his home studio to view his artworks. I am struck by the rooms (and sheds) full of serious modernist looking paintings and sculptures. I’m off on a tour of Stevan’s works which find their roots in some of my favorite modern art movements. The sorting, packing, and unpacking appears an art in itself. Stevan makes his paintings and sculptures outside in his backyard. An expressionist’s dream place; dozens of colourful paint pots, spilled paint, brushes bearing histories, boards, canvasses; all in a state of flux. I’m emphasising Stevan’s workplace as his commitment to the process of making is key to the works. The paintings are physical, he wields bold stokes of paint mixed with sand; the colours are intuitive and refined from hours of experimenting. They are weighty and worked over, carved into. At this early stage there’s no concern about their display, the engineering issues will be solved later. Stevan is not concerned with decorative design trivialities; art is serious and life is short! Free from trying to imitate reality, images will emerge by working quickly, chancing his arm for up to ten hours a day in pursuit of making something worthwhile.

Stevan reflects on the suffering of humanity generally, and specifically with his own and his brother’s experiences of mental illness. These reflections are most obvious in his text and sculptural works where raw emotions and connections to life’s difficulties confront the viewer. Stevan takes neuroleptic drugs to manage schizophrenia. “I’m limited in the things I can do, and making art provides balance. It’s the only avenue I have to do something with my life due to my illness” Stevan says. He goes on to say that “happiness can occur in the brain by working, and it can create an uplifting feeling”. Placing this idea into an art historical context Stevan refers to Louise Bourgeois who made a text work titled Art is a Guaranty of Sanity.

A keen student of art history, Stevan and is well aware of his influences, American Abstract Expressionists, German Neo-Expressionists, London Modernist School, Arte Povera. My attention turns to an early art school photograph, a self-portrait, limbs splayed, taken at the Botanic Gardens. The motifs in the paintings I now see as figurative, and the recent works becoming more recognisably descriptive of the body. I’m visually being led with clues towards future works.

Robert Habel

Stevan Howison, Non Objective Painting No. 115, acrylic on board.

Stevan Howison, Study from Nude Elk Two, acrylic on canvas.