Not Just A Shadow by Elyas Alavi / Whale-Backs and Miscellaneous Forms by Edwina Cooper & Ash Tower

Elyas Alavi

Elyas Alavi’s practice is interdisciplinary bridging elements from poetry to visual arts, from archive to everyday events with the intention to address issues around displacement, trauma, memory and sexual identity.

He reflects upon his background as a displaced Hazara (a marginalized ethnic group originally from Afghanistan), and use his particular experiences and contemplations as an epistemological model for the dislocation of people and collective memories.

Alavi graduated from a Master of Visual Arts at the University of South Australia in 2016, and has exhibited at Mohsen Gallery (Tehran), Robert Kananaj (Toronto), IFA (Kabul), Firstdraft (Sydney), as well as Ace Open, Felt Space, Nexus Arts (all Adelaide).

a moon rises over a desert cemetery

her glow reveals the gravesites of five cameleers

their memories stretched across oral history

and through the pages of forgotten books

amongst sand and rock, their bodies

buried in foreign soil, so far from family

held in the unfamiliar

through imagination and culture, Elyas

connects with countrymen from long ago.

customs and sounds, ring through memory

stories resurrected for the present

a cultural connection, through language and faith

the self embodies the past

While the story of the cameleers now rests within land

there are other stories that run far deeper

that have been carried through song

old history becomes creation

blakfella’s often say, ‘you only need to listen to the land’

we forgot to mention that land is also

constantly listening to us

in his trek to the desert, Elyas did exactly that

a surrendering and waiting for land to hear his call

it delivered to him a story he could not find in books

history becomes spiritual and tangible

not only is this work an ode to the cameleers,

but it also speaks to an artist’s journey

to connection with land

where all stories are present

as an Indigenous person

i know that our connection to land is paramount

it holds us together, while providing nourishment and song

i wonder how the cameleers felt being so

disconnected from their own country

the daily struggle to remain connected to oneself

while living and working in a country that

does not reaffirm your identity

land that doesn’t hold you, a racist

colony that doesn’t want you

truly made to feel as much as a foreign

outsider as one could be made to feel

the pain and frustration of racial

hierarchies, echo through to today

deep within detention centres where ‘australia’ continues

to illegally hold refugees and asylum seekers

white ‘australia’ policy is alive and well

white supremacy continues to make us all sick

oppressed peoples always seem

to find each other

banding together in workplaces,

within prisons and institution

even within the remote

desert, Aboriginal peoples

and the cameleers found

their connection, their love and even family

still to this day, some Aboriginal families

carry the last names of the Cameleers

commonality, an embrace of solidarity

the outsiders bond leading to things far more beautiful

than the colony could ever imagine with its poisoned mind.

many moons have risen and fallen over

the graves of the cameleers

casting shadows over the bright red soil

the salt pans, glisten in the moonlight,

shimmering right back at the moon herself

like most things in the desert, the graves look lonely

but they aren’t, they are kept company

by the stories within

stories and memories that live long enough to inspire

kin to visit and to create artwork in the hope that those

stories and memories get to live a little bit longer

Dominic Guerrera

Dominic Guerrera is a Ngarrindjeri, Kaurna and Italian poet, writer and curator who lives on Kaurna Yerta.

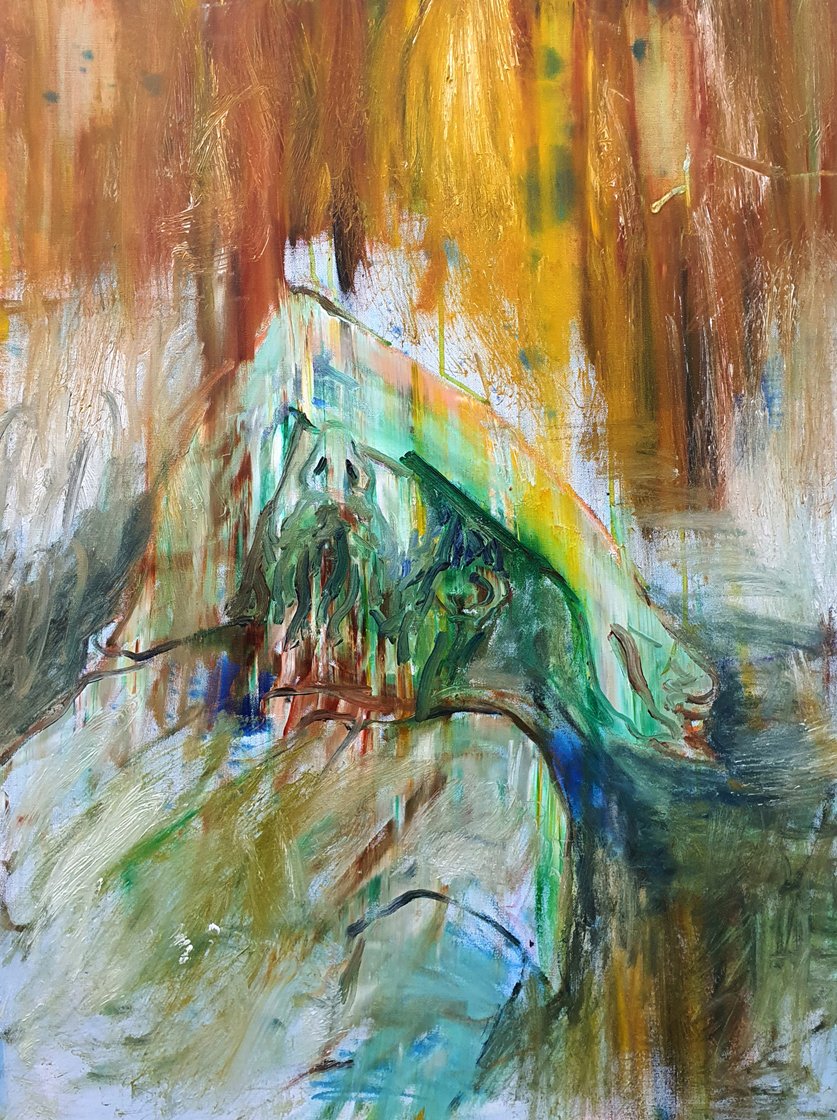

Elyas Alavi, Seeing, 2021, oil color on canvas, 2 panel, 76 x 110 each. Courtesy the artist

Edwina Cooper & Ash Tower

Edwina Cooper’s sculptural and installation based practice is influenced by her experiences as a sailor, with a continued interest in the methods for human experience and interaction with oceanic thresholds. Cooper’s practice investigates human inferiority in the face of oceanic immensity and our attempts at fathoming oceanic and other water spaces.

Cooper has undertaken residencies in Australia, France and Canada and has drawn on these experiences, as well as self directed nautical research, to produce artworks that have been exhibited widely in South Australia and interstate. In addition, Edwina has been longlisted for the 2022 Aesthetica Art Prize (UK).

Ash Tower (he/him) is an Adelaide-based artist and researcher examining how knowledge is produced in visual culture. Tower is currently an ACE Open Studio Resident for 2022 and has exhibited nationally, including 'Via Purifico' at Pig Melon in Boorloo/Perth, 'The Burning of Vision' at the Floating Goose Studios, and 'Protocol' at Cool Change Contemporary as part of the Unhallowed Arts Festival. He has also exhibited at PICA (Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts), the CACSA Project Space, and Carclew Youth Arts. In 2015 Tower undertook a residency at 'SymbioticA: The Centre for Excellence in Biological Arts'.

Encroaching mountains of sand peer over backyard fences in Fowlers Bay. Like an impending tidal wave, its appearance serves as a reminder to the isolated and exposed village that an impressive natural force is right next door. Dunes have migrated in the region considerably in recent memory. Original parts of the town — High Street and a cluster of homes known as Kent Town — are already buried. A dozen historic dwellings have been swallowed by sand, with Kent Town’s remaining chimney tops last seen in the 1970s. The re-routed road that replaced High Street now faces a similar fate. Robyn Wallace strides through her quaint seaside caravan park. “Visitors are always fascinated by the fact Kent Town is completely buried under the sandhills — and it could happen to us if things don’t change significantly,” she says. “Clearly when we bought the park [the dunes] were something that we investigated, they’re very close to the town. She says movement among the dunes is common. “Our water is located several kilometres out in the dunes, and when we first took over the park we used to constantly get lost trying to find our well. You’d drive through the dunes and have to change your track every time.”

Along with the changing dune system, Fowlers Bay has vastly transformed to serve an array of purposes over time. Native title belongs to the Mirning, Wirangu, Kokatha, Maralinga Tjarutja, Yalata people who have long spiritual connections to the area. There are traditional stories of whale dreaming at Fowlers Bay, where Mirning people would call whales from the edges of the Great Australian Bight. Leonard Hardy and Robyn Wallace drive through a dedicated path in the dunes carefully, with native coastal plants wobbling on plates in the back of their four-wheel drive. They arrive at a portion of the dunes that’s most critical to stabilise in order to preserve their main road and infrastructure. Leonard has already started dragging up green waste and large tree branches — anything to hold down the moving sand. “It’s imperative we start now and keep it up and stabilise those dunes where they are” Robyn says. Leonard presses moist sand around a new sapling. “You’ve got to do everything for yourself out here, so it’s everybody on board. It’s how you achieve something.”

Words from Evelyn Leckie

Excerpts from an ABC news story by Evelyn Leckie published in September 2021, available at https://www.abc.net. au/news/100440452. Reproduced with permission.

Dunefield, Fowlers Bay, 2022, courtesy the artists.

Still from composite satellite footage, Fowlers Bay Dunefield, courtesy Professor Patrick Hesp.