Flotsam & Jetsam

Carly Tarkari Dodd

Cheryl Hutchens

Deborah Prior

Jacqueline Bradley

Kay Lawrence

Makeda Duong

‘Flotsam and jetsam’ is an expression used to describe an accumulation of ‘odds and ends’. It also refers to two different kinds of shipwreck. ‘Flotsam’ is the cargo that floats ashore after a shipwreck and ‘jetsam’ is gear discarded to lighten the load in the face of danger. One is unintentional and the other intentional. The distinction between the two is important under maritime law because of ownership; flotsam may be claimed by the original owner, whereas jetsam can become the property of whoever discovers it. The sad reality today is that our oceans and waterways are scattered with debris, most of which is plastic that is incredibly harmful for the environment.

For the past few years Adelaide textile artist Cheryl Hutchens has been hand-punching out sequins fabricated from her household recycling. “Sushi boxes are one of my favourites” the artist admitted during a studio visit, as she lovingly cradled an old shiny black and gold plastic sushi box. Her new work takes her obsession with patterned plastics even further with the insertion of quirky, playful, and poignant details – “no” in red lettering, recycling symbols, dairy cows, an adorable pig with a blue bow. Inspired by the photographic series by Chris Jordan, documenting decomposing albatross chick bodies on the shores of Midway Atoll. As Hutchens described, “who died with their guts full of plastic (albatross parents mistake rubbish for food and collect from ocean and feed to chicks).” Likewise, Bird Guts and Purge sampler I are illustrative of the grotesque internal organs and stomachs littered with plastic. Hutchens’ versions are beaded beauties, somewhat reminiscent of nanna’s embroidered handkies but with loud clashing colours that bombard the senses. Their beauty is a front for the sad and starling reality beneath.

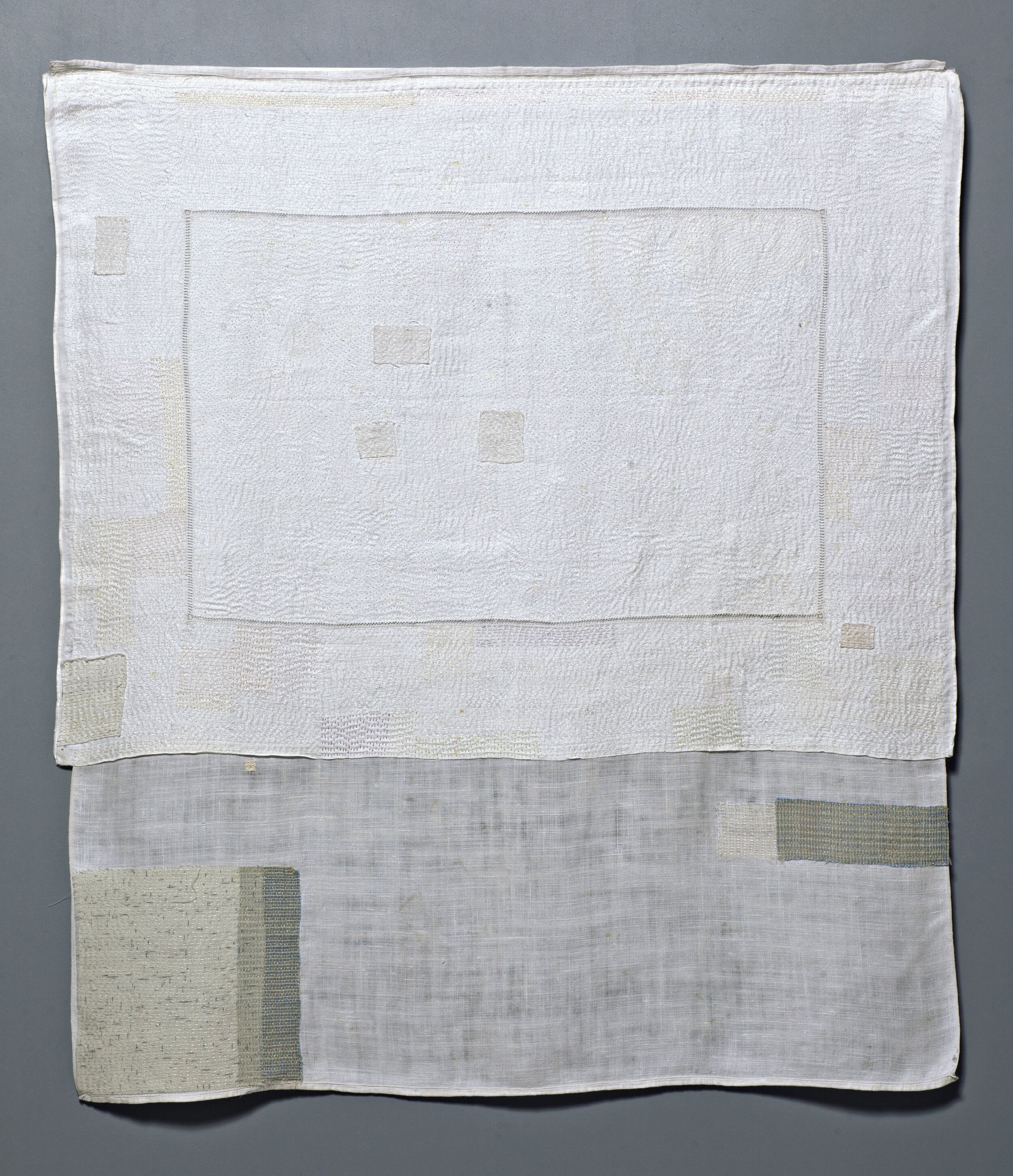

Also working with found, humble, and familiar household items such as tablecloths, blankets and cloth napkins is Deborah Prior and Kay Lawrence. Both artists have gone through a process of mending simple fabrics. Their bodies of works are like sewn up skins that are beginning to heal. Lawrence’s six textiles were made between 2012 and 2016 from found and hand-me-down odds and ends that the artist collected from around the world. Lawrence explained, “handwoven cloth from India and indigo dyed cloth, Japanese Kimono fragments.” She has repaired them all slowly and carefully with running stitch “the simplest of stitches”. Prior has collected all the pieces of a pair of blankets that have been used in various projects and even been scrap material “used to plug holes!” This exhibition has been her motivation to find all the repurposed sections of blanket and slowly and painstakingly put the blankets back together so that (maybe) they can be whole again. But as the artist confessed: “no time or pain or effort can repair things exactly as they were.”

As with many craft-based arts practices they take time and care, are often handheld and handmade, laid in laps, taking over living rooms, studios, kitchen tables and beds. They are lived with and worked on for significant amounts of time and through a labourious process of piecing, stitching, threading, weaving, knitting together these odds and ends become part of something greater. A message, a story. Carly Tarkari Dodd, proud Kaurna/Narungga, and Ngarrindjeri artist based in Adelaide, “mix[ing] traditional and contemporary techniques, to produce works that are conceptually and culturally driven.” Here she combines traditional Aboriginal weaving with European royal portraiture traditions, placing herself within woven frames, adorned in woven raffia crowns. Her regalia and lukewarm expression challenge “onlookers to consider Australia’s history, […] to take ownership of what is the strongest symbol of colonialism: The Crown.” Her frames draw on lived history and injustices experienced by her people. She frames herself as a strong, regal, and Sovereign First Nations Person.

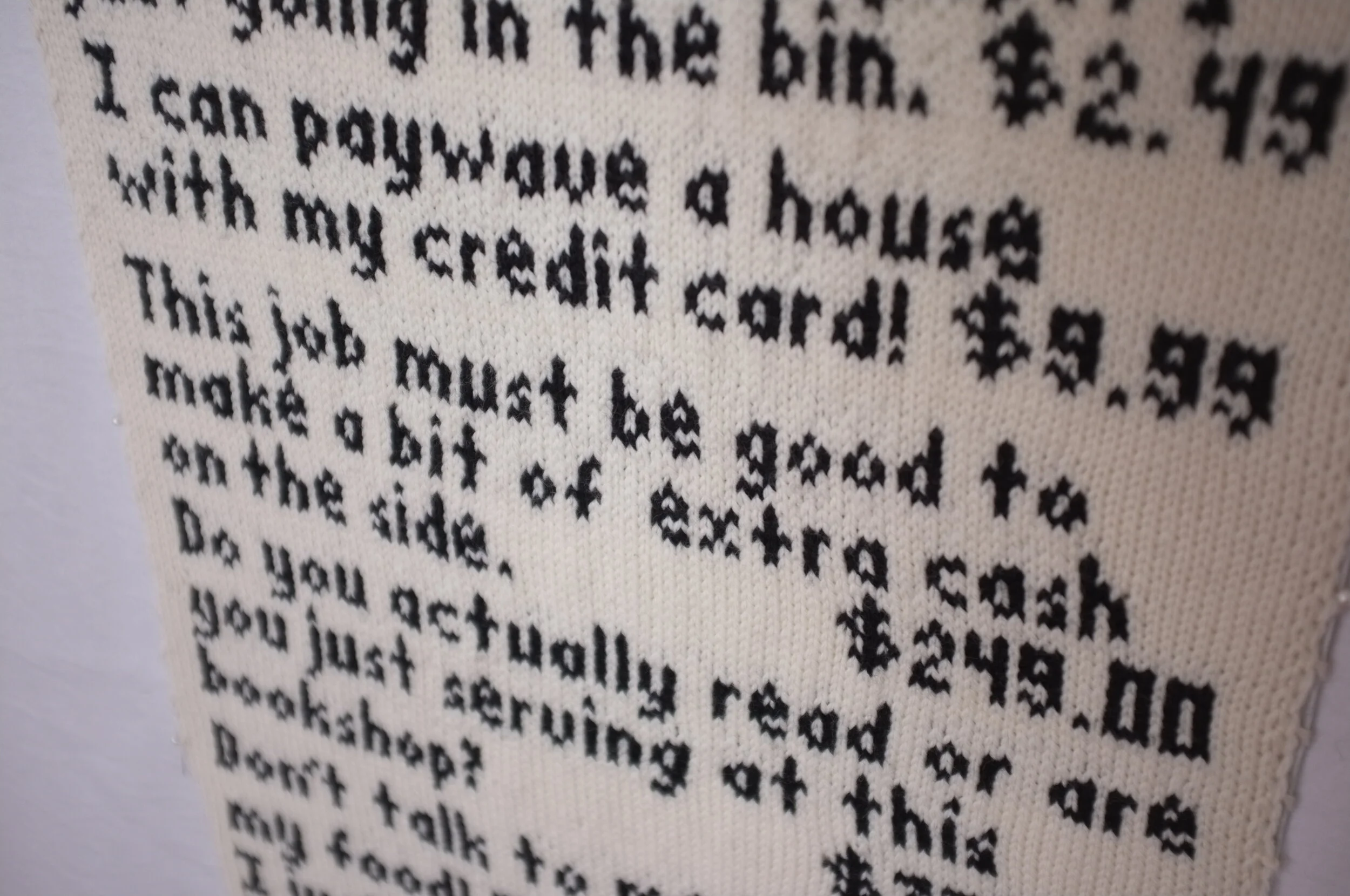

Makeda Duong also makes art that directly references her lived experiences and her identity as a Vietnamese Australian woman. Her work explores experiences of inequality and absurdity while working in customer service roles. She knits real quotes from real customers, highlighting class division and the superiority experienced in a world where the customer is always right. When talking about the Shit Customers Say series the artist said, “I don’t want it to be negative necessarily, I want it to be quite funny.” Through humour she draws the audience member in and takes them on a journey, a day in the life of a customer service worker.

Also beckoning closer examination is Canberra based installation artist Jacqueline Bradley’s Apricot Niche sculpture consisting of a custom-made linen and wooden structure holding eight hundred individual apricot stones. The perfect semi-circle of fabric suspended across flag posts is the ideal viewing platform for private inspection. The stones are not alive nor dead, holding the potential for an entire orchard neatly compartmentalised. Bradley creates order from chaos and organises an immense ecosystem one bite-sized nook at a time. The artist beautifully described:

“Backyard landscapes are intimate moments of control within controlled suburban blocks. In these sites, eating and feeding and growing and rotting unfold in close proximity. This small space is filled with chickens and orchards, eggs and apricots, shells and stones. Things replicate and reproduce, and with each cycle the site is remade.”

Whether remade or repaired, needle-worked, gathered, or woven, found, or reused, these textiles hold memory, time, life, and experience. Each tells a different story, if only we would take the time to listen and look a little closer, we might make a new discovery of our own.

Precious Cargo

Polly Dance

Jacqueline Bradley, Apricot Niche, 2020, Timber, linen, apricot stones, cotton wadding and linen/cupro, 210cm x 160cm x 70cm, photograph Brenton McGeachie.

Carly Tarkari Dodd, Blak Royalty (detail), 2021, raffia, photograph, 60 x 45 cm

Kay Lawrence, White on White (detail), 2015-2106, Running stitch, cotton thread on found linen & cotton cloths (tray cloth, tablecloth and Japanese cloth), 78 x 87 cm, photograph Michal Kluvanek.

Cheryl Hutchens, Purge sampler I (detail), waste plastic, found handkerchief, beads, thread, 25 x 25 cm. Photography courtesy the artist.

Makeda Duong, Shit Customers Say (detail), 2021, hand knitted merino wool, felt, floristry wire, 215 x 47cm.

Deborah Prior, Long Lost Flock (detail), 2021, woollen blanket, yarn, found foot stool, dimensions variable.