From Czechoslovakia with Love by Jenna Pippett

Jenna Pippett

Graduating in 2012 from Adelaide Central School of Art, completing a Bachelor of Visual Art with Honours. Pippett was selected for Hatched: National Graduate Exhibition at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art. She also exhibited in the 2013 Helpmann Academy Graduate Exhibition, in which she received the City of Adelaide Award. In 2017 Pippett was awarded the Eran Svigos Award for Best Visual Art at the Adelaide Fringe.

Exhibiting in a solo capacity at Adelaide City Council’s Art Pod (2013, SA), FELTspace (2014, SA), Constance ARI (2014, TAS), SEVENTH Gallery (2016, VIC), Sawtooth ARI (2017, TAS), ACE Open: ACE Across (2017, SA) and Kings Artist Run (2018, VIC).

Pippett has also participated in several group exhibitions, including at Adelaide Central Gallery (SA), Hobiennale (TAS), Greenaway Gallery/GAGPROJECTS (SA), FELTspace (SA), Adelaide Town Hall (SA), Australian Experimental Art Foundation: Odradek (SA), Screen Space (VIC), Abbostford Convent (VIC), Video Platform: Art Stage Singapore (Singapore) and Art Stage Jakarta (Indonesia), Muratcentoventidue: Arte Contemporanea (Italy) amongst others.

In 2019, Pippett worked as an Exhibition Attendant for the Australia Pavilion at the Venice Biennale through the Australia Council for the Arts. An active member of the local arts community, Pippett served as a Co-Director of FELTspace (2015-18), a nationally recognised Artist Run Initiative and is a visual arts peer assessor for Carclew. She currently sits on the Artist Advisory Group and the Board for (SALA) South Australian Living Artist Festival and has been employed as a Gallery Assistant at Hugo Michell Gallery since 2015.

The formation of Czechoslovakia in 1918 saw the creation of a new national anthem. Instead of forging a new musical identity, the anthem was an abrupt combination of two verses from separate nationalist Czech and Slovakian songs. The Czech verse was from a song titled Kde domov můj, translating in English to Where My Home Is. During the era of this anthem, the combined territory had a tumultuous history, occupied by the Nazis during the Second World War and subsequently becoming the Czechoslovak Communist state from 1945 until the 1990s. When the countries divided in 1993, so too did the anthem, with the new Czech Republic retaining only the first verse. While the stanza is a relic of centuries-old national pride, the fleeting one-verse song suggests something incomplete, fractured and divided.

Where My Home Is provides both the title and the soundtrack to Kaurna Country Adelaide-based artist Jenna Pippett’s new video work. This video sits at the heart of the exhibition From Czechoslovakia with Love. Pippett’s decision to use this amputated Czech national anthem as the score to the video work is layered with significance. It alludes to the physical and cultural displacement of Pippett’s grandparents and mother, who fled the Czechoslovak Communist regime in the late 1960s to resettle in Australia. Instead of accompanying an event of national significance, the anthem scores a different kind of ceremony. This ritual is Pippett’s Czech grandmother, Ilona Kminek, known as Babi, lovingly and methodically creating schnitzel for her family to share. This ritual of dousing chicken breasts in flour, baptising them in an egg wash and adorning them with crumbs before frying them in a bath of oil until golden-brown is a comforting, repetitive act which gives an intimate view into émigré life. The video work Where My Home Is captures every minute step of the process with the lingering view forcing a reconsideration of domestic acts, like cooking. While cooking can be seen as a mundane, common occurrence in everyday life, Pippett reframes it as a performance of identity – drawing our attention to the legacies informing the act, like the repeating recipes inherited from family members and creating dishes which signify cultural heritage. This act of service is also one of care and love, with Kminek passing on these rituals to her grandchildren.

Pippett’s oeuvre draws on both anecdotal and researched accounts of her family’s past, often activating these histories through processes of reenacting and reprising. The artist recently applied for the release of historic documents detailing the ‘criminal activity’ of her grandparents. These documents were compiled by the Statni Bezpecnost StB (Communist Secret Police) following the family’s escape from Czechoslovakia. The release of these documents can be understood as a form of repatriation, returning the private information unknowingly garnered and stored by the secret police back to the family. The blurred boundaries between private and public information under the totalitarian regime, as elucidated in this document, inspired Pippett’s series of large-scale digital prints.

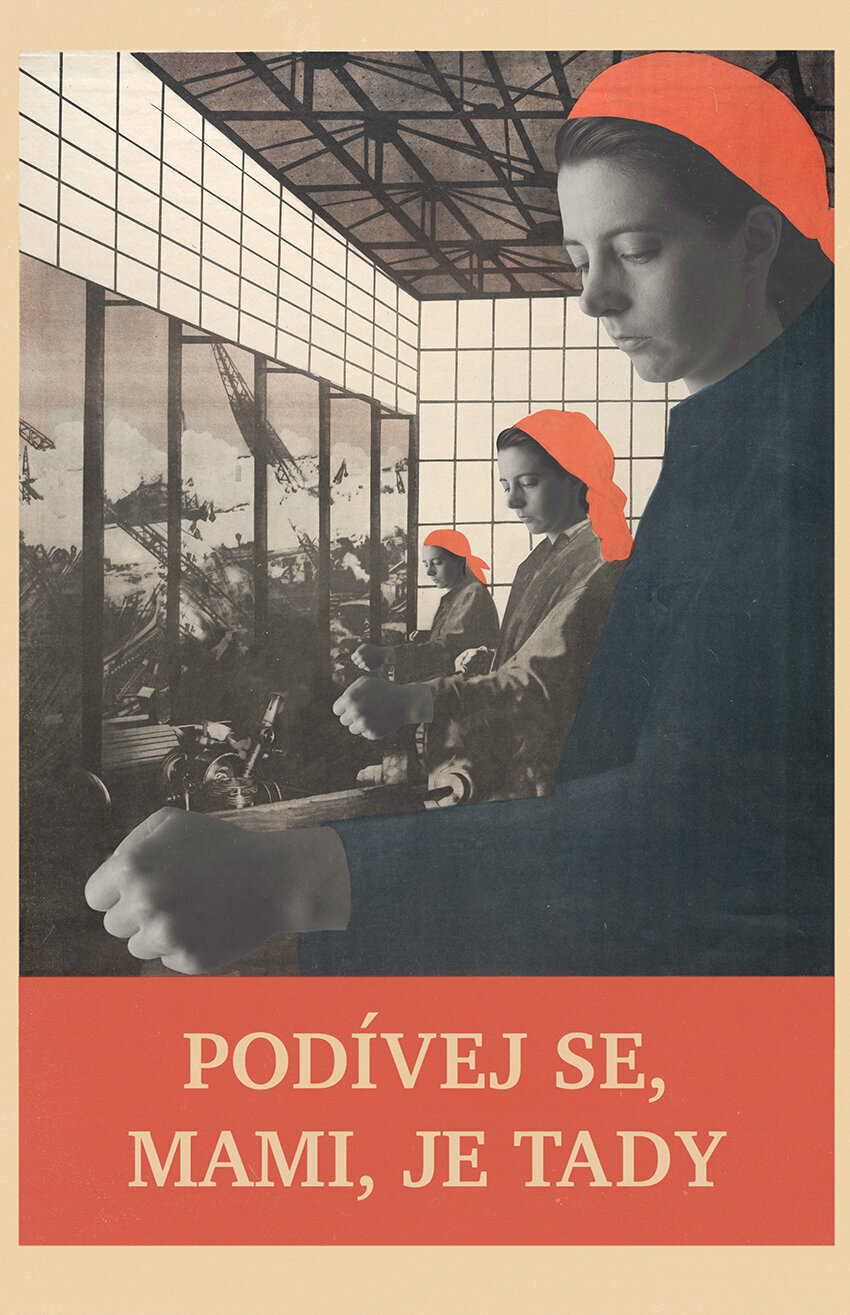

Eight posters featuring larger-than-life figures line the gallery walls like sentries, positioned as if to overpower or intimidate the viewer. However, instead of unnerving the audience, these works elicit a sense of delight as we enter a world in which Pippett wittily plays ‘dress-ups’ with history. The works directly appropriate iconic Czechoslovakian Communist propaganda posters. Originally, these posters would have sought to encourage the general public to act ‘patriotically’ and to live by government-sanctioned ideals of “work, strength, peace, people, happiness, prosperity”. In place of the idealised images of upstanding communist citizens, Pippett humorously embodies and enacts these stereotypical personas. These include an optimistic and youthful couple, a patriotic soldier and a stern old woman. In performing these personas, Pippett forms a lineage with Australian photographers who also interact with history by re-staging iconic imagery, including Anne Zahalka and Julie Rrap. The repetition of the artist’s face throughout the series shows a physical interaction with the imagery that shaped her grandparents’ lives, and as a result, directly influenced her own life.

In place of the didactic slogans found on the original posters, Pippett draws on a highly personal vernacular of Czech phrases she learned during childhood. These phrases form part of her second-generation Australian vocabulary, consisting predominantly of English with slippages into her family’s mother-tongue. Some of the posters speak to Pippett’s early Czech education from relatives, like learning the names of animals. Others are phrases spoken thousands of times by her grandparents like “why won’t you eat the cake?”, “leave her alone!” or “you monkey!”. This language is imbued with childhood memories and speaks to familial dynamics filled with good-humoured bickering between siblings, grandmotherly scolding, ample servings of food and laughter. By replacing the communist mantras with phrases associated with caregiving and formative education, Pippett subverts the intent of the original poster, transforming it from a call to action to a powerfully personal archive.

Where My Home Is

Yvette Dal Pozzo

Jenna Pippett, Zvířata: kočka, pes, beránek, žába (Animals: cat, dog, lamb, frog), 2020- 21, digital print, 84x130cm.

Jenna Pippett, Proč nebudeš jíst dort? (Why won’t you eat the cake?), 2020-21, digital print, 84x119cm.

Jenna Pippett, Look, mum is here, 2021, digital print, 110x71cm.

Jenna Pippett, You little monkey Jenna, 2021, digital print, 110x71cm.